TEXASGRAD

By Max Auger

(discovered by Christopher Blair)

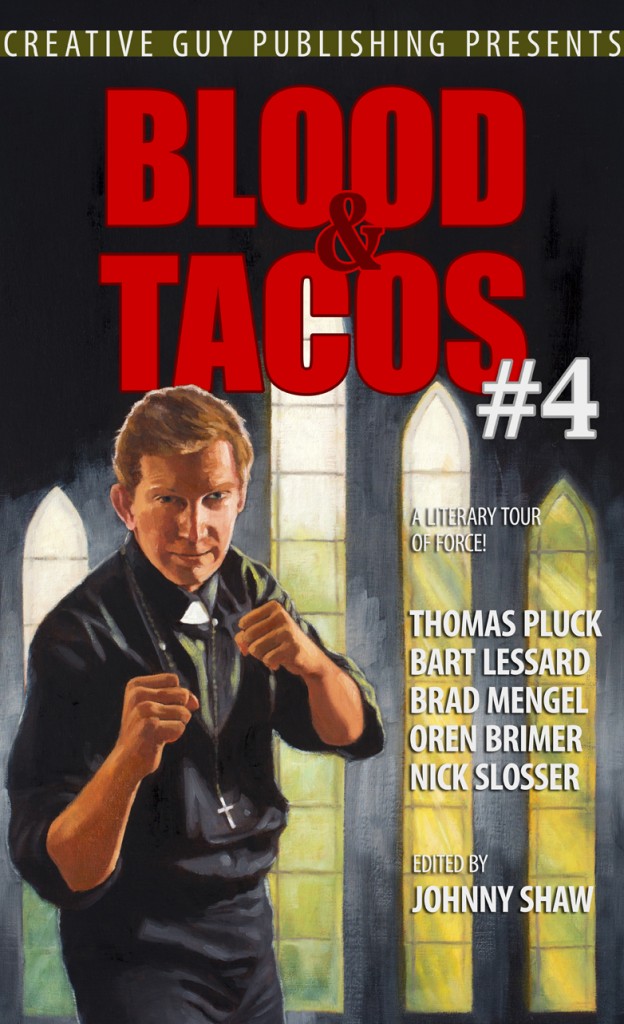

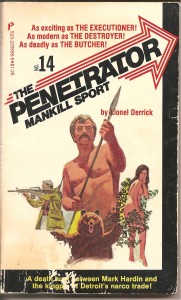

CHRISTOPHER BLAIR found this Reagan-era classic at the Coos Bay Swap Meet on the coast of Oregon. Even among survivalist training manuals, Laser Tag accessories, and tarnished throwing stars, the embossed mushroom cloud and hammer and sickle on its cover were hard to miss. Very little is known about the author Max Auger; we do know that this is his first printed effort and a prime example of the ’80s post-apocalyptic sub-genre of men’s adventure.

That sign’s in Russian!

At first, Capt. Mike McCreary thought the binoculars were playing tricks on him. He pressed himself further into the rich Texas soil and leaned forward into the dry grass like a crouching lion. He blinked and looked again.

It was too much to take in. Less than a mile away lay his hometown, its neat, clean buildings untouched by the Russian and Chinese death that had streaked in a year before. In fact, the town looked just the way it did when he’d left Sunny here to be safe. There it was, just west of the school: the little house they’d bought with his promotion pay. Sunny was in there. Waiting for him, but thinking he was dead.

Every fiber of his body wanted to run to her, to tell her that he’d survived. But his military training told him to stay put.

The farms and fields encircling the town of Wrangler Plains looked like a pale green quilt. He saw the workers and tractors and clouds of dust, working together to bring in the harvest, the familiar motions of bending and lifting, of wiping honest sweat from an honest man’s brow. He knew that his childhood friends were down there, the ones who’d stayed home, just a few minutes’ sprint from the gentle rise where he now lay.

If not for the sign, printed on a bright piece of plywood planted on the shoulder of Highway 27. In bright red letters:

Добро пожаловать на

Wrangler Pавнинами, Техаса!

население 1845

And printed in smaller letters:

Скоро будет переименован работника

поля, как только наши товарищи

освободиться в их умы и сердца от гнета капитала!

McCreary handed the binoculars to Spec. Charles Whitefeather, crouched beside him like one of his Comanche ancestors stalking a buffalo. Whitefeather shook his head politely. “No thank you, Captain.” McCreary cursed his insensitivity: Of course, Whitefeather wouldn’t need the binoculars. Not with his hunter’s eyes.

Instead, he handed them to Private Billy LaRoy to his left. Next to LaRoy, Spec. Brad Hawker, the sniper, took it all in through his scope.

“I don’t understand, Cap,” LaRoy said, “Why are all them R’s backward? I may not be no college boy, but I know when letters ain’t right.”

“That’s Russian writing, Private,” McCreary said. “It looks a little like ours, but it ain’t.”

Whitefeather hit the dirt next to McCreary. “Tanks!” he hissed.

McCreary grabbed the binoculars from LaRoy, just as Hawker muttered, “Five of ’em. No six. No, seven! To the right of the church, off the main drag.”

Son of a bitch: Seven tanks were rolling across Hank Steinhoff’s alfalfa field. Suddenly, they stopped about fifty feet from the First Church of Christ, a row of fat iron turtles. In unison, their turrets began to swing. Even a mile away, the squad could feel the tanks’ metal rumbling in their bellies.

“This doesn’t make sense,” McCreary muttered. “The Reds weren’t supposed to this far north. Intel said we stopped ’em at San Antone.”

“Those tanks are huge,” Whitefeather said, “I ain’t seen nothin’ like that this close. Not even doing Black Ops in Europe. I feel an ill wind blowin’, Captain.” He paused, then added: “This is bad medicine.”

They all knew the truth. Only LaRoy, as always, clung to the bright side. “Maybe they’re PT-76’s on a scouting run. We have to get back, tell General Pearce that the Russians are coming.”

“They’re not 76’s,” McCreary said. The dread in his voice was thicker than Texas tea. “They’re not scouts. Those are T-80’s. Seven T-80 main battle tanks. The Russian’s aren’t coming.” He ran his hands through his thick black hair. “They’re already here.”

McCreary looked at Whitefeather. The big Comanche had closed his eyes, smelling the breeze coming in from town. What secrets did the air hold? It was best not to ask Whitefeather when he went to… that other place.

“Hawker,” McCreary said. “You speak some Russian. What does that sign say?”

“Welcome … to Wrangler Plains … Texas,” Hawker recited. “Population… 1,845.” McCreary felt a stab of annoyance. He didn’t need some grunt with a Russian grandmother to tell him the population of his hometown. It was 1845, same as the date Texas joined the Late Great United States.

McCreary swung his binoculars back to the tanks, parked close to the church where he’d married Sunny Summerville. There, a mere feet from the menacing T-80’s, were the front steps where he’d worn his dress blues and held Sunny’s hand next to Pastor Joe.

Hawker continued: “The rest of it says: Soon to be renamed… Fertile Worker… Fertile Worker … something… Fields! Fertile Worker Fields! …”

McCreary squeezed the binoculars when he saw the distant form of Pastor Joe. The reverend sprinted down the steps and ran toward the tanks, waving his hands. The hatch on one of the turrets popped open. A gray-suited Russian tanker appeared. The Russian lifted his arm. It held a pistol.

“…renamed… as soon as our comrades … free themselves…”

McCreary watched Pastor Joe, unafraid, stop shy of the lead tank. He held something up in his hands. McCreary couldn’t make it out, but he knew he held a Bible. The same one that he and Sunny had laid their hands on to become man and wife. But as blessed as it was, no Bible could stop a bullet.

The Russian tanker fired his pistol. Whitefeather whispered something sacred and sad in his own language.

“…free themselves… in their minds and hearts … from capitalist oppression!”

As if on cue, the tanks fired over Pastor Joe’s crumpled body. Licks of orange erupted from their barrels. The church exploded silently, slats of pure white wood spinning in godless flame.

Three seconds later, the sound arrived at Lonestar Tactical Unit 1 and shook them to their very souls.

![]()

McCreary slept the fitful sleep of a fighting man. He dreamed, as he always did, about the week before the attack. He’d known something was afoot. Troop movements in East Germany. Chinese maneuvers in the Formosa Strait. Soviet maneuvers near Turkey, practice amphibious landings in Egypt, just miles from the Israeli coast.

He hadn’t talked to Sunny in three weeks. Command had canceled all leave, and McCreary hadn’t been out of Silo J-47 long enough to make a single phone call. Not that he’d have been able to, anyway, with everything locked down. Hours in the terminal he shared with Lt. Jansen. As Jansen blabbed once more about the whole thing being a Communist plea for attention, the Squawker had jolted them out of their routine.

“Juliet! Juliet-Four-Seven! Priority Message Charlie!”

He and Jansen had sprung into action, confirming the missile codes. They’d just inserted the keys when their station, buried two hundred feet under the frozen North Dakota plains, began to rock and shimmy. The lights flickered. Surely they had seconds to live. All thoughts of conscience and doubt were swept away as he and Jansen turned their keys.

On their command, in silos buried all around them, five Minuteman III’s breathed dragon-fire and arced into the sky, bound for glory.

“They’re away!” Jansen yelled. “That’s what you get for stabbing us in the back!” He turned to McCreary, “It’s been an honor serving with you, Captain.”

Then, the lights went out and the bunker shook. A great roaring rip in the walls and ceiling. The smell of cold and earth. Everything around them collapsed. Somewhere up there, the world exploded and North Dakota—and America herself—was bathed in an unholy nuclear fire.

The Chinese—McCreary later learned—had initiated the plan’s first phase: introducing a program into the Defense Department’s computers that replicated itself, like a disease. Almost like a computerized… virus. And like a virus, it had spread over the newly installed Inter-Network that the technocrats had insisted would keep America safe. Instead, their newfangled computers had given the Communists their gateway. Linked and spreading the contagion, every weapon that carried a nuclear tip—from bombers to missiles—was rendered inoperable. Some Asian wiseacre had added the final indignity: Whenever a command was given to launch a plane, or a missile, the intercom played a tinny alien tune that only a handful of the crews recognized as the Chinese national anthem.

Then, the Chinese launched Phase 2: Sending their fifty Long March rockets high over the United States, to detonate two hundred miles up. The explosions fried every electronic circuit in the country. The Chinese hadn’t tried to flatten the cities and the missile silos.

That part of the plan had been the Russians’ job.

For reasons that he never figured out, only McCreary’s silo—representing just five missiles out of thousands—had managed to go aloft that day. Whether they reached their targets, McCreary doubted he would ever know.

But the dreams only touched on that part of the story. Whenever he slept, his dreams always eventually led to Sunny—her long honey-colored hair, her narrow waist, her virtuous smile. Her delicate hands that could squeeze a trigger and pick off a jackrabbit at a hundred yards.

It was Sunny, the cheerleader who’d waited for him after football games. Sunny, who wore that frilly skirt, who loved him enough to let his hands roam, but loved God and her virtues enough to make him wait. Sunny, who wore his ring as he went into Air Force Pararescue. Sunny, who talked him through it on the phone after he told her he’d washed out. Sunny, who told him to come home and marry her. Sunny, who didn’t get mad after their honeymoon to Corpus Christi, when the Air Force decided that they still owned him and stuck him in the ground in North Dakota.

And of course, it had been Sunny who compelled him to claw his way out of a crooked elevator shaft and to survive everything afterward.

![]()

General Pearce studied the reports on the card table he’d been using as a desk since Omaha. Sweltering in the General’s tent, McCreary stood at attention, while his men—LaRoy, Whitefeather, and Hawker—stood behind him.

“This report you filed,” Pearce said. “It doesn’t make sense. The First Cav and the rest of III Corps stopped the Russians and Mexicans at San Antonio.”

“How do we know for sure, General?” LaRoy blurted out. “We’ve had spotty radio traffic from that sector since last week!”

McCreary winced. LaRoy had never learned when to shut it.

“I don’t remember asking you a thing, Private!” the general barked. He shot to his feet and glared at McCreary. “Once again: An Air Force flyboy and his ragtag squad of enlistees are trying to tell me how to link up with III Corps.”

“With all due respect, General,” McCreary began. “This ragtag squad of enlistees and I have been the eyes and ears of this brigade since Omaha. We’re telling you what we saw. An entire Russian tank battalion has taken over my town. I need to go back there.”

“No,” the general said. “We can’t risk it.”

“Can’t risk it? We need intel!”

The general waved his hand over the card table. “We have intel! You’ve done your job. No need to put your squad—and the rest of us—at risk. So far, the Russians don’t know our exact location. We’ve tied up their air assets over New Mexico, which is why they haven’t spotted us.”

“You don’t know that!”

“McCreary, if these Commies catch you, they’ll know we’re moving south with brigade strength. At the very least, we wait for the 101st. Their radios are working. They’re in Mississippi and heading this way.”

“General, if I may be so bold—” McCreary began.

“No! That’s my decision,” Pearce said. “I’m sorry about the Russians in your town, Captain. I am.” He added, with a soft tone that did nothing to assuage McCreary’s worst fears: “They may be godless cowards, but I’m sure your wife is alive. You’ll see her soon. Just be patient.”

“General, please—”

“Dismissed!” The four men stood abruptly at attention, and in unison, turned and banged through the door into the hot Texas sun.

![]()

The four of them—McCreary, Whitefeather, Hawker, and LaRoy—entered their tent and dropped their gear on their bunks. McCreary fumed. He had made certain assumptions on returning from their scouting run: Certainly after reading their report, Pearce would authorize another trip south.

But he hadn’t.

Usually McCreary respected the old man’s caution. It had held them at the Missouri River, just before a squad of Russian-made Mexican Hind helicopters had swooped in and wiped out the 173rd, waiting to rendezvous on the other side. The general’s instincts had kept five thousand men from leaving what remained of Lincoln, Kansas—just avoiding the swarm of radioactive twisters south of Wichita Falls.

But now, the general was being too cautious. McCreary and his men were the whiskers of a lion that was meant to pounce. Not cower in a scrub forest west of Waco.

Behind McCreary, Hawker disassembled his rifle. “I’m sure she’s all right,” he said.

“You know it, Cap” LaRoy chimed in. “That Sunny of yours sounds tough as nails. Don’t you worry about all the things them Russians do to womenfolk whenever they take ov—”

“That’s enough, Private!” Whitefeather barked with uncharacteristic ferocity. The dreamcatcher above his head swayed from his voice.

But McCreary heard none of this. His complete focus was on his bunk. Lying on his bunk was a sheet of paper. A string of words formed a row, neatly typewritten.

In Russian.

“Hawker,” McCreary said in a voice he barely heard in his own ears. “I need you to read something for me.”

![]()

McCreary and his men hunkered behind the same rise where they’d spied Wrangler Plains the day before. Fall was coming, and the faint trace of their breath rose above them in the chill, dawn air.

“You men don’t have to be here,” McCreary said. “We’re defying orders. If you double-time it back to base, they might not notice you’re gone.”

“Too late now, Captain,” Hawker said. “You know we’d follow you to hell and back.”

“That’s right, Cap,” LaRoy said. “Ain’t no Commie bastards gonna rape your town, no sir.”

Whitefeather breathed a patient sigh. “Don’t worry about your wife, Captain. We’re on my former hunting grounds now. The earth speaks to me. The Great Spirit will keep her safe.”

McCreary was moved beyond words. But it wasn’t time for emotion. They had a job to do: to rescue Sunny, and, God willing, to kill some Ivans in the process.

“Captain!” Hawker hissed, squinting through his scope. “A work detail! Ten… no, twenty civvies!”

McCreary raised his binoculars. A couple dozen people walked out to Bill Dolan’s wheat field. They carried scythes and hoes. Old-fashioned tools. McCreary thought he recognized a couple of them. There was Ida Grange, who’d owned the diner on Route 283. She wore a plain gray dress, the likes of which McCreary had never seen. And Bill Dolan himself, dressed as strangely in drab clothes, like something out of Fiddler on the Roof. He wore a wool cap. McCreary could only make out a faint red shape, front and center on the cap.

A star.

“Captain,” Whitefeather said, squinting into the distance, “Company.”

McCreary moved the binoculars back and forth. “Where?”

“Five guards,” Hawker said, “To the right? See ’em? … Mexicans. And two Russians with ’em.”

Sure enough, a squad of five Mexican soldiers, unshaven, their fatigues crumpled and disheveled came into view. Fifty yards away stood a pair of Russian privates, distinguished by their light blue shirts, shouldering their AK’s, smoking cigarettes and laughing.

“Backstabbers!” LaRoy muttered.

“Let’s move into position,” McCreary said. “Whitefeather, you and LaRoy circle around. You handle the Mexicans. Hawker and I will take out the Russians.”

“I don’t know,” Hawker said. “It’s not the objective. If we shoot and miss—”

“Then don’t miss,” Whitefeather said. “When the Mexicans start to dance, sir, that’ll be your cue.” The big Indian and LaRoy were already moving through the tall grass like a couple of leopards.

McCreary and Hawker had plenty of cover as they moved. A rusted combine. Three boulders. A pumphouse. Before too long, they crouched unseen only five yards from the Russians, who chattered away in their dirty, oily language. Beyond them, McCreary could see the Mexican guards, lounging next to their truck. One had his hat down over his eyes. The others leered at a group of teenage girls. The biggest soldier, with a huge, black mustache, catcalled one of the girls in Spanish. She didn’t look up, only hoed the ground faster.

McCreary raised his M-16 and aimed it at the Russian on the left. Hawker had his rifle up, peering unnecessarily though the sight. At this range, Hawker would have been automatic with a blindfold. Maybe he was just being cautious.

The big soldier moved toward the girl. “¡Señorita!” McCreary heard him say. “Eres hermosa. Venir aquí!”

His last words. The soldier’s head silently exploded. The sound arrived a half second later. The Russians jerked to attention like startled antelope.

Then, everything happened fast.

The big Mexican fell to the ground like a headless sack of tamales. His men jumped to their feet. Two of them grabbed for their rifles—then began their silent, jiggling dance of death. The remaining two ran toward town.

McCreary drew a bead on the nearest Russian’s chest and fired. The M-16 kicked against his shoulder with a reassuring thump. The Russkie was dead before he hit the ground. A millisecond later, Hawker fired at the Russian on the right—and missed.

The scrub oak tree behind the Russian split in two. Hawker’s Russian looked around with big, cowardly eyes. He could see neither McCreary nor Hawker—and turned to run.

Goddammit, Hawker! McCreary thought. He raised his rifle and dropped the Russian with a single shot to the back of the head. McCreary felt the slightest tug of sadness. The Russian kid had looked all of nineteen, and now he lay dead in the dirt, with the front of his head replaced with an exit wound.

McCreary tried to quash any regret: They invaded my home. Not just my country. The Commies are in my home town. Sorry, Ivan: You had to die.

Across the field, Whitefeather and LaRoy chased down the remaining Mexicans. LaRoy tackled the slower one and drove his Ranger’s knife into the back of his head. He jiggled in the dirt like a beetle in some sadistic kid’s bug collection. Whitefeather had caught the other one. McCreary, far out of earshot, knew what was happening: The big Comanche was drawing his knife across the Mexican’s throat, but whispering words of a hunter’s respect into his ear as blood flowed from his body like a sacred stream.

“I’m sorry, sir,” Hawker said. He looked seriously dejected. “I’ve never missed in my life. Too close quarters, I guess. But that’s no excuse.”

McCreary patted him on the shoulder. “It’s all right. I never make mistakes, you know?”

“You’re a good man, Capt. McCreary,” Hawker said softly. “I won’t let you down again.”

“I know you won’t,” McCreary said. “Let’s join the others.”

Whitefeather and LaRoy were already at the girls. “It’s all right,” Whitefeather said to the tallest one. “We’re Americans, like you!”

“That’s right, miss,” LaRoy said. “Head up that road. There’s an American base not ten miles away. They’ll take you in and keep you safe. You’ll see!”

Here came Bill Dolan, running toward them, with Ida Grange on his heels, holding her skirt up from the ground. They’d dropped their tools and looked relieved to see them. Actually, that wasn’t right. They didn’t look relieved. They looked scared.

That wasn’t right, either. They looked angry.

Dolan and Ida yelled incomprehensibly. LaRoy tried to calm them.

McCreary arrived at the group. Sure enough, that was a red star on Dolan’s cap. And why was Dolan yelling at them… in Russian?

“Chto vy delali?” Dolan cried out. “Eti soldaty byli nashi druzʹya! Vy uzhasno bandity!”

“This doesn’t make any sense,” Whitefeather said, drying his knife on his fatigues.

Just then, fifty Russian soldiers rose from the summer wheat, surrounding them. Each soldier brandished an AK-47. The rifles’ magazines curled toward McCreary’s team like black fangs. A faint breeze blew, hissing through the grain menacingly. McCreary felt awash in an ocean of dread. Even the wheat had turned against them.

“Captain McCreary,” an accented voice said from behind a tree. They all turned. Out stepped a tall, Russian officer. He wore plain, pressed olive-colored combat fatigues. Only the three pale stars on his shoulders betrayed his rank. “Thank you for joining us on such a fine morning as this.”

“Who the hell are you?” LaRoy asked.

“I am General Yuri Azov of the Soviet Army,” the general said. “And you will do well to check your tone with a superior officer, Private LaRoy, of Lewisburg, West Virginia.”

“How do you know my name?” LaRoy asked.

The general ignored him. McCreary dropped his M-16 on the ground as the general and two soldiers approached. He motioned to the others to do the same. They obeyed—except for Hawker, who kept his sniper’s rifle slung over his shoulder. Good old Hawker, McCreary thought. A sniper to his dying day.

“How I know is not important,” the Russian general said. “Not nearly as important as the honors we will bestow upon Lieutenant Hawkerov … of the KGB.”

The sniper that McCreary had known as Hawker clicked his heels, stood at attention, and gave the general a crisp salute.

“Lt. Hawkerov,” the general said, “thank you for bringing Captain McCreary to enjoy the benefits of our worker’s paradise. And thank you for delivering my note, as well! Such a brave, loyal son of Kiev!”

“Hawker!” McCreary cried softly. The sniper glanced at McCreary for the briefest of moments. What was that in his eyes? Was it shame? Were Communists even capable of such an emotion?

“I am happy to do my duty for the Motherland,” Hawker said in English.

“As am I,” the general said.

Azov raised his pistol. McCreary recognized it as a Nagant M1895. A seven-shot, gas-sealed revolver, issued only to the top Communist Party members. Azov was the real deal. And he demonstrated it by shooting the sniper in the chest. Hawker—Hawkerov—crumpled like the traitor he was.

McCreary’s mind spun. “W-why?” he asked, just as a rifle butt struck the back of his head.

![]()

McCreary regained consciousness, pain glowing bright yellow in his skull. He tried to move his arms, but couldn’t. They were stretched behind his back. He opened his eyes to sunlight streaming through tall windows. McCreary recognized the office of Mayor Todd Houston. Same oak paneling, same fancy desk the size of a Mississippi River barge. But the walls were adorned with posters, of proud workers facing the sky under the same backward Cyrillic letters that Hawker had translated the day before—

Hawker. Goddammit, Hawker!

Whitefeather and LaRoy were similarly seated, their arms tied behind their chairs. They were awake. LaRoy had two black eyes. The scrappy little private had apparently tried to fight them off. Whitefeather didn’t appear to have a scratch on him. The Russians probably knew better than to tangle with the big Indian.

Other than two Russian guards at the door, they were alone.

McCreary scanned the room. His eyes stopped on a huge oil painting, five feet high and three feet wide, hanging on the wall behind the desk.

The painting looked like something out of the 1700s. It showed a blonde woman in a blue dress, her hair tied behind her head, standing in a field of flowers. A basket of blossoms hung from her elbow. In the distance, a Russian church with three onion domes sat under yellow clouds and a red, setting sun. McCreary couldn’t take his eyes off the woman.

Sunny!

The door to the office opened. General Azov wore a more ceremonial uniform, whatever it was that the Russians called their Class A’s. His boots shone and thumped on the old oak floor, every step a gunshot.

“I see you’re awake, Capt. McCreary,” the General said.

“You seem to know me quite well,” McCreary intoned. His skull throbbed with every syllable.

“I’ve known all about you for years.” Azov said, pulling an olive-colored folder off his desk and opening it. “Captain Jacob McCreary, United States Air Force… born on March 2, Texas Independence Day … Eagle Scout… joined the Air Force’s Pararescue division for training, but forced out with a knee injury obtained when rescuing a comrade from a tangled parachute line. … Reassigned to the 91st Missile Wing, where you performed with distinction.”

“Hey, how do you know all that?” LaRoy asked.

Azov continued. “Before assuming command of this glorious invasion of your … doomed empire, I was second-in-command of the KGB. It was my job to know about every American missile officer. I know every detail, Capt. McCreary. I’ve followed your career. And your personal life. I was amazed at the similarities of our ambitions. Of our character. And most importantly, the fact that our wives appeared so… identical. So naturally, I studied you. And her. With great interest.”

“What’s that supposed to mean?” McCreary asked.

“Oh, Captain. We shall deal with that soon enough,” Azov said, “We are discussing a clash of civilizations. Mighty empires, meeting on the field of battle! Our Chinese allies, tired of being a third-rate power. Mother Russia, impatient that it has taken seventy years to bring capitalism to its knees. And so, we have Chinese Plan Chang Alpha 7. To erase the threat posed by the American nuclear arsenal. And it worked with 99.9999 percent accuracy.”

Azov walked to Mayor Houston’s liquor cabinet. McCreary remembered the cabinet from the day he’d made Eagle Scout at 17, the day Sunny had given him that chaste kiss on his cheek. That day, the Mayor had toasted young Jake McCreary with a shot of whisky. The Russkie general had replaced the mayor’s Kentucky gold with bottle after bottle of Stoli.

The general poured himself a glass. “Our plan was foolproof, except for you. You, Capt. McCreary, commander of the only American nuclear assets that were able to leave their silos on time. You, who drilled your men to check and recheck their systems at all hours. You, whose computers were constantly resetting themselves, as per your orders. And when our blessed day arrived, it was your men who possessed the necessary reaction times.” The tone of his voice darkened. “Still, of the five Minuteman III missiles that you launched, four were destroyed by our laser-based missile shield—”

“Missile shield!” McCreary muttered. “You got Washington to sign ours away in that last treaty!”

“Backstabbers!” Whitefeather said. “We Americans always honor our treaties!”

“Be that as it may, gentlemen,” Azov continued, “The only surviving Minuteman III missile—serial No. 8534-Dash-A—was enough to destroy its target: my village of Fertile Worker Fields, fifteen kilometers east of Kiev.”

“That’s ludicrous,” McCreary said. “Americans never target civilians. The Dash-A was aimed at a radar station—”

“—less than a kilometer away from my village—” Azov turned and gazed at the oil painting above the fireplace “—and my beloved Svetlana.”

McCreary lowered his head and studied the planks between his boots.

“The day I assumed command of our hidden forces in Laredo,” Azov said, “waiting for our orders to invade the United States, I learned that our motherland had escaped unscathed—except for the missile that you launched. Imagine having everything you loved wiped out by the treacherous, glowing heart of an American atom.”

Azov, still holding his glass, walked slowly across the floor to where McCreary sat.

“When I heard from a minor KGB operative, Lt. Hawkerov, that you had survived the strike on your base, I was seized with anger, a thirst for revenge—and a clarity I have not known since I was a young man. I made it my duty to take from you what you took from me.”

“No…” McCreary whispered.

“Conquering this sector of Texas was easy,” Azov said. “I was then able to locate your hometown, Capt. McCreary. To find your beautiful wife. To make her and all of the members of this … beautiful community… the beacon of Socialism that my home had been!”

“You Communist bastard!” McCreary spat.

Azov chuckled. “Do your American friends working in the fields not look happy? Do they not look fulfilled? A little hypnosis here, a little torture there… but at the heart of it all, Communism is simply a fancy word for ‘sharing.’ And you have been sharing your beautiful Sunny—or should I say, my Svetlana—with me for the past three months.”

His voice dropped further, into an oily and sultry tone. “Her skin… so very soft on these … lonely Texas nights.”

“Nooooooo!” McCreary screamed.

“If my Moscow command knew what I was doing in this town,” Azov said, “they might strip me of command. All they know is that I have taken Wrangler Plains—I mean, Fertile Worker Fields—as my command post. A staging ground for a thrust into the breadbasket of the future United Socialist States of America. But the inspired loyalty of our new comrades, my taking of a field wife—this is my personal effort.”

“And of course, you had to destroy the church,” McCreary hissed.

“We are not animals, Capt. McCreary.” Azov said “We waited. And when Lt. Hawkerov let us know that you were en route, I decided that the church would be the perfect demonstration. The perfect incentive for you to visit us again.”

“You’ve disobeyed orders,” McCreary snickered. “Your own superiors can’t trust you.”

“As you disobeyed orders to come here,” the general said. The ice in his glass clinked. “We’re not that different, you and I, Capt. McCreary. We love our countries. We love the warrior’s path. But at the end of the day, we are men who live by our own rules. ”

Calm down, Jake old boy, McCreary thought. There’s a way out of this. Don’t let him get to you.

And in his calm, McCreary’s plan gelled. He could taste its humble brilliance. It tasted like freedom.

“That’s where you’re wrong, General,” McCreary said. “I’d never take another man’s town, much less his wife. I’d never engineer a sneaky invasion of another country. That’s not the American way.”

Azov drained his glass and leaned forward toward McCreary. “You Americans,” he said, “always so idealistic.”

“Yes,” McCreary said, “idealistic—and very good at untying knots. Especially us Eagle Scouts.”

Azov’s eyes twitched in recognition that he’d made a grave error. Rope flew and McCreary’s fist circled in from the right and smashed the good general’s cheekbone. Azov crashed into the desk and crumpled to the floor. McCreary stood over Azov, fists ready.

“Get up, you Commie sonofabitch!”

The Russian guards at the door had already pulled their sidearms and had them leveled on McCreary. “Ostanovit!” one of them cried. “Ostanovit, vas kapitalisticheskaya svin‘ya!”

McCreary turned to them. “Go ahead. Do it,” he said. “Shoot me, you godless puppets! I haven’t got all day.”

The arrows that pierced the windows of the mayor’s office hit the guards’ chests so quickly, it appeared to McCreary that they’d burst from their hearts. Both Russians slowly sank to their knees.

Still tied to his chair, Whitefeather let out a shrill cry. “It’s my brother warriors, Captain! They heard my call on the spirit winds!”

Outside the mayor’s office, three sets of dissimilar sounds rose: Russian cries of alarm, sporadic AK fire… and a hundred Comanche war whoops.

McCreary had the big Indian untied in seconds. Azov was struggling to his feet, but the general collapsed again, moaning, struggling to unholster his Nagant.

“That was some punch, Cap!” LaRoy cried. “Look at that Mongol bastard! He can’t even stand!”

Whitefeather untied LaRoy. They each took one of the guard’s sidearms. “You better do the same, Captain,” Whitefeather said. But McCreary was way ahead of him. He grabbed Azov’s pistol from the general’s weakened grasp.

Outside, the battle raged. Through the windows, McCreary caught glimpses of action: scrambling Russian soldiers, flashes of gunfire, mounted Comanches in deerskin and full regalia, chasing them down. Gunfire. The twang of bowstrings and the thud of tomahawks. Screams of panic and pain.

McCreary pulled the dazed general to his feet.

“Leave him!” Whitefeather said. “The sacred battle is joined!”

“No,” McCreary said. “You and LaRoy go. The general and I have someplace to be. Don’t we, General?”

LaRoy was beside himself. “Let’s go, Whitefeather! I always wanted to be an Indian brave! Whoooooop!” And out they went, leaving McCreary and the General.

“On your feet,” McCreary said grimly. “Take me to my house.”

![]()

McCreary’s homestead lay to the north of town, away from where the battle between the Russians and the Comanches was playing out. McCreary had to resist the urge to shoot Azov, rescue Sunny on his own, and sprint out of town. But he couldn’t leave his men, and bringing Azov back alive might be the only thing that would keep Gen. Pearce from court-martialing him on the spot.

As McCreary moved Azov through the abandoned streets, they saw only flashes of action through streets and windows. Tanks rumbled. Russian APCs sped along, surrounded by bands of jogging, terrified soldiers. None of them seemed to notice that McCreary had their beloved commander at gunpoint.

They neared McCreary’s home. There was the mailbox, painted bright white. There was the same grass. The same picket fence. The same gate, the last thing McCreary had made before shipping off to North Dakota. The only thing that was missing was the American flag that always hung from a bracket off the porch.

“She’d better be alive,” McCreary said.

The general had said nothing since leaving the mayor’s office. In fact, nothing since McCreary had socked him. But now, the general seemed to perk up.

“Oh, she is alive, Jacob,” Azov said, as he walked through the gate. “If things had gone as planned, she’d be baking bread like a good Russian wife. Waiting for her husband, me, to show up. To enjoy a good meal. Then enjoy her, afterward.”

“Careful, General,” McCreary said. Through the windows, McCreary could see that everything in the house had changed. Gone were the photos of his family, of Sunny’s family, the oil painting of Jesus that Sunny had painted for the state fair. Instead, McCreary could make out mostly bare walls, adorned only with the occasional image of Marx, Lenin, and old Papa Joe himself.

Azov opened the front door. They walked inside. There was no smell of bread.

“Where is she?”

“In our bedroom.”

McCreary responded by shoving the barrel of the Nagant between Azov’s shoulderblades so hard that the general staggered toward the stairs. Up they went, one step, two, the steps creaking. In the distance, a tank fired. The house shook.

“My Svetlana!” Azov called out. “I have brought you a guest. He is… so… very eager to see you.”

They reached the top of the stairs. Down at the end of the dimly lit hallway was the door to their bedroom. Where McCreary and Sunny had learned about the sacred covenant between man and wife.

“You’ll be happy to know, she’s been very resistant to my charms,” Azov said, a few feet shy of the door. “It’s taken much… persuasion to even get her to look at me, but never without distrust in her eyes. And I must admit that she has resisted even my more… skilled methods.”

“Shut up,” McCreary said. “Open the door.”

The General obeyed.

The bedroom McCreary had shared with his wife had been stripped down to three things: a four-poster bed, a Soviet flag hanging from a six-foot staff in the corner, and Sunny herself. McCreary’s wife was unconscious and pale, tied on the bed, clad only in the virginal white nightgown she’d worn on their wedding night. Her hair was a curly blonde halo around her sleeping head.

He couldn’t restrain himself any longer. McCreary shoved the general aside and raced to Sunny’s bedside. “Sunny! … Sunny, it’s me! It’s Jake!”

Sunny opened her eyes. They were sunken and tired—from what, McCreary didn’t want to know—but they were the same bright blue. They lingered on his. He saw a flicker of recognition—and a flash of red in their reflection over his shoulder.

Instinct. McCreary turned and fired. Again, and again, and again. McCreary barely registered the sight of Azov, brandishing the Soviet flagstaff as a sharpened weapon. It was a sea of red—flapping fabric, and the general’s blood.

Azov staggered backward. Blood poured from his surprised mouth. But somehow, the general lurched forward again. McCreary fired twice more. And again. Then, remembering that the Nagant held seven rounds, he saved the final shot for a spot right between Azov’s dark, beady eyes.

Azov’s dying body lurched backward, his shiny boots clattering against the hardwood floor. Back he flew against the window, and through it, shattering the glass, and tumbling to the yard below.

Sunset. McCreary carried his wife’s limp form across the high school football field. He could barely take it. The unholy lines that passed on the turf at his feet. Those aren’t yard lines, he thought. The goddamned Reds turned this Texas high school football field into a soccer field. Soccer!

Suddenly the sound of hoofbeats erupted. McCreary turned. Here came Whitefeather, astride a brown and white paint, with streaks across his face, the color of Russian blood. Behind him was LaRoy on a gimpy palomino and no less than a hundred Comanche warriors. In prewar life, they’d been proud working men and boys on the Reservation, content to do whatever it was Indians did. But now, they proudly had revived the spirits of their ancestors.

“The battle is ours, Captain!” Whitefeather cried. “The Russians didn’t quite know what to make of this outfit.”

“Well, a fitter bunch I never did see!” McCreary said, happy but weary.

“Captain, look!” LaRoy held aloft a long knife. “They made me an honorary Injun!” McCreary nodded, his eyes drifting to the dark, dripping mats that hung from their saddles.

McCreary didn’t want to know.

“We have to get moving,” Whitefeather said. “The Russians retreated, but you know they’ll be back. We have to get back to General Pearce and tell him what we know.” The big Indian turned and raised an AK-47, and let loose a war whoop. The warriors behind him responded in kind.

McCreary turned and hunkered down to his wife. “Did you hear that, Sunny? We have to get going. … Sunny! Sunny?”

Lying beautifully on the grass, Sunny opened her eyes.

“Sunny! Did you hear me?”

His wife smiled faintly.

“Da,” she said.

THE END

Christopher Blair is a teacher, freelance writer, and former crime reporter. In addition to being raised on ten-for-a-dollar used paperbacks, he grew up on a nutritious diet of comic books, Stephen King stories, and pure cane sugar. “Texasgrad” is his first published short story.

Pingback:First of Many (I Hope) | cpb