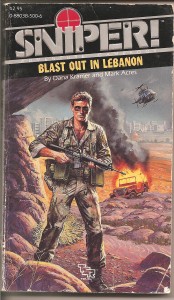

SNIPER! Blast Out in Lebanon (by Dana Kramer and Mara Acres)

Text taken from an interview with Agent “Sniper” by Matthew C. Funk, 2012, at Sniper’s home in West Palm Beach, Florida.

Our decisions can’t change the course of the world.

I used to believe different. I used to accept, as a part of myself essential as a heartbeat or a sinew, that we can change the planet.

Choose door one rather than door two, and kings are torn from the throne. Nations fall. Freedom rings.

Or not. You fail and your failure means the turn of the world shifts.

CIA operatives buy into that faith—that “for want of a nail” pipe dream.

That faith made me capable of surviving Beirut in ’87. It’s what sent me there in the first place.

A black-budget agent for the CIA has to buy into it. It’s not just why you do what you do. It’s who you are: More important than truth. More important than morality. More important than life itself.

You lie, fight, and die for that faith—that perfect promise that global “win or lose” comes down to your decisions.

Then you get old. You watch Al Jazeera English and eat the same Stouffer’s meals you did when you were a kid. You listen to your West Palm Beach condo association argue the same way you listened to Hamas and the PLO leadership argue. You read The New York Times, and the religious hatreds are the same—only the names have changed.

You watch the YouTube generation grow up, enlist, and die by the same roadside bombs.

And you realize:

The world’s turning doesn’t change. All the faith there is can’t change that, no more than faith could make the world flat.

Your decisions have only one effect: life or death.

You kill someone or you don’t. You get killed or you don’t.

You take two fistfuls of the Ativan prescribed under your CIA health care plan and wash it down with a fifth of absinthe. Or you keep turning the pages, reading on through the chapters of your life, even through the story never gets different.

I miss Beirut sometimes. I was Jason Malone then.

Malone knew what he was doing. He was changing the world, one choice at a time.

It was Beirut, 1987.

It may as well have been 2007. Or 1967. Or 7,000 years ago. Beirut doesn’t change much.

Sure, the language on the signs goes from Phoenician to Latin to Arabic to French. And yeah, the roasting meats now turn upright and run on electricity. It’s Christians against Muslims against Jews now.

But in 1500 BC, it was Egyptian Ra-worshippers against Hittite storm-god followers. The aroma of meat roasting on a spit still slathered the air. The language—the first record of Egyptian and Hittite language together; the Amarna letters—was still discussing war.

I was sent to stop a war. The conflict between Druze Christian militia, Israeli hawks and dozens of Islamic extremist groups was on the brink of boiling over. A peacemaker, David Saxon, on a secret mission for the CIA, had been captured.

Nobody knew by who. Or why. Or to what end.

But my handler at the Company knew that if the captors got David Saxon to talk, it would all end badly.

Fingers would be pointed just to prove nobody was backing down. Israel, the Druze Christian militia of Beirut, the Muslim extremists—all would blame each other of trying to mess up the conflict.

I had to find David Saxon before those names got out. I’d save him or kill him, before whole nations had an excuse for epic bloodshed.

Right out the gate to Beirut Rafic Hariri International Airport, I should have known someone would have to bleed.

Right out the gate, someone took a shot at me.

I allow myself just one drink these nights.

I swirl the ice in the glass and watch it melt, as ice is wont to do. The waves roll in, roll out, and I think.

I think on the inevitability of these things.

I checked into my hotel in Beirut and went to meet an arms dealer, Hammadi. It was part of my cover: I would act as if I had something to offer Hammadi’s clients on all sides of the conflict. They, in turn, could hopefully give me a lead on David Saxon’s whereabouts.

After I checked in, I checked if I had someone on my tail.

If I hadn’t watched my back, I’d have never met the Israeli agent. For all I know, he could have been killed by the Brotherhood of the Green Flag—the Muslim fundamentalists whose compound I went on to find David Saxon at.

If the agent had died, I’d have hooked up with the Green Flag directly instead. I’d have been led into an ambush. I’d have had to fight my way into their compound rather than have Israeli intelligence parachute me into it.

If I’d been ambushed, I could have shot my way out. If the Israeli followed me undetected that night, maybe he’d have killed me.

It all comes down to who took a bullet first.

They named me “Sniper” at the Company because I shot and hit first. If I hadn’t, my name would have ended up as ash in a Langley burn barrel.

But I lived, and so did Israeli intelligence agent Aaron Ben-David. The KGB-connected Green Flag thug who tried to lead me to an unmarked grave, Omar, he died.

And David Saxon lived. I shot my way through a West Beirut militia ambush. I could have shot my way out of an East Beirut Israeli ambush. I broke into the Green Flag’s compound, grabbed Saxon and shot my way out of there too.

Life or death, that’s the only difference. The men trying to kill me were killed first.

Life or death, that’s all that mattered. I lived. David Saxon lived. His peace deal lived.

And in the end, it didn’t matter at all.

At the West Palm Beach condo neighborhood meetings, they call me That Shithead.

I earn it. I argue every proposal. When some blue-hair in a Chanel pantsuit raises a voice of opposition against them and looks to be winning her point, well, I argue against her too.

The men who called me Malone in Beirut are all dead or retired. Either way, the people we were are gone from the Earth.

At Senior Speed Dating, the ladies call me Mr. Mystery.

They do it with a wink or a coy downward look. I look like I keep my secrets and they pick up on that. I use that secretive air to pick them up.

Truth is, I could care less about my secrets. The bearded men and boys in keffiyeh who died to keep those secrets, died to protect a policy that is three generations outdated.

At the Company, they still call me Sniper.

I go to the reunions in Annapolis every five years with all the other code names. There’s always less hair and more skin cancer, but the suits never change. And we drink designer beers and shoot the BBQ-laced breeze about black ops, just like former football stars turned car salesmen would talk about their big plays and how they got laid because of them.

Only, people got laid out in morgues, rather than laid. People who we used to know, who no longer are.

The Middle East still is, and still is at war.

In the valley outside Beirut, Goliaths and Davids still do battle.

In Beirut, Israeli intelligence and Druze militias and Muslim extremists still play the game, only the names have changed.

Their faith continues, but mine’s gone.

Beirut was blown up three times, but it’s still here. America is still here and it is still at war in lands where only the language on the signs change.

I keep turning the pages, but the story is never any different—only the adventure is gone.

Matthew C. Funk is an editor of Needle Magazine, editor of the Genre section of the critically acclaimed zine, FictionDaily, and a staff writer for Planet Fury and Criminal Complex. Winner of the 2010 Spinetingler Award for Best Short Story on the Web, Funk has online work indexed on his Web domain and printed work in Needle, Speedloader, Off the Record, Pulp Ink and D*CKED.