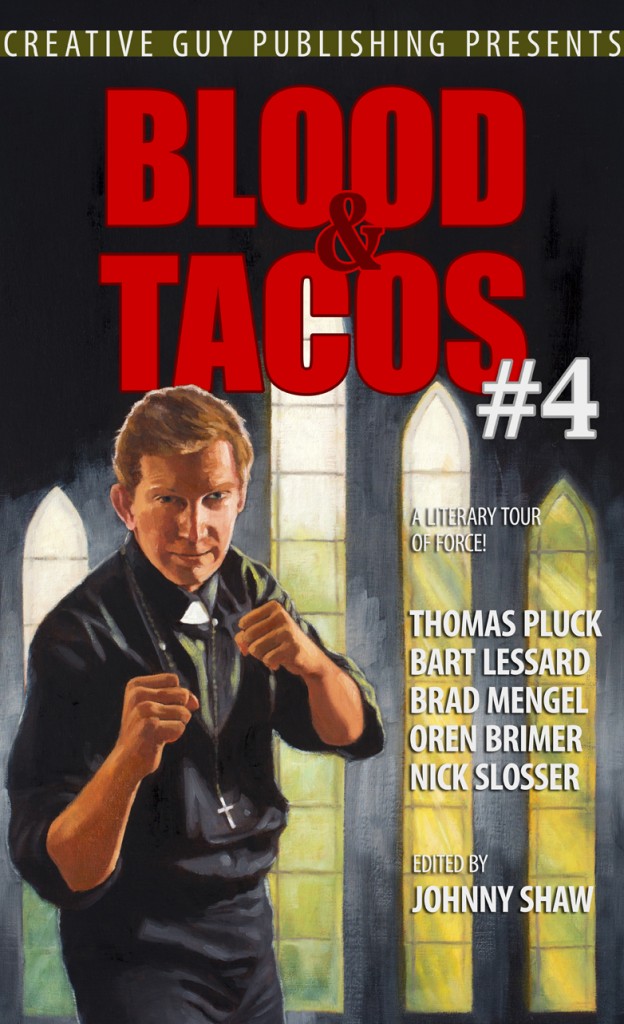

DOPEHOUSE INFERNO (Abridged)

By Milt Walsh

(discovered by Bart Lessard)

The street-tough priest and heavyweight boxer Father Dukes graced several softback originals stuffed into ferry terminal twirly-racks of the 1970s. But owing to the publisher’s noncommittal efforts with glue binding and a soda-pulp paper stock that might best be described as “twiggy,” only one fragmentary copy of this particular outing is known to have survived. BART LESSARD found it tucked into the dirty insulation behind his broken water heater. He painstakingly reassembled the gist of the missing parts by posting a question thread to the “pefo” forum on Craig’s List, then trying again under “libtards” and “over 50.”

West 44th Street, Delaware City. On a map, a simple line. On the ground, the brink of hell. Once it had marked the edge of the meatpacking district. But the cattle trains had stopped coming in, the A & P began to stock wheat germ, and the breed had changed along with the times. Gangs, pushers, junkies, hookers, pimps, longhairs, immigrants, radicals, catamites, welfare cheats—these were the new flesh. With something like pride they had kept the old nickname for their new haunts: the Killing Floor.

The border was clear even without a map to mark it. On the far lane of West 44th, long cars cruised by slow—candy-colored cars with furs inside, cars with gleaming hubcaps, cars with chandeliers, cars that bounced. The stoops held a crowd, colored men in suedes and furs and pegged pants and purple fedoras. A purring crew of whores and punks met their every whim. Men in stained raincoats roamed the concrete in between, eyes cast down, seeking a chance, a fix, a woman, a pretty boy, an exit. Every car stereo and pocket hi-fi blared the savage thrum of disco.

But none of this netherworld dared cross the fading paint that marked the middle of West 44th. Not one pimp sedan ever made a left across the other lane. Something held them all back. Kept them in check. Told them, here, and no farther.

Nowhere was the gutter stench stronger than in the loom of the burnt-out tenement. It stood in the center of the block, and it had no right to stand at all. Like the furnace of hell had in the time before time, it had caught fire. And like hell promised to, it had people in it yet: shadows glimpsed through the broken windowpanes, mysterious comings and goings. At any hour day or night the walks around it teemed with the lowlife, peddling dope and lust, preying on the weak. The building should have been condemned, scrubbed clean with a wrecking ball, but building inspectors never came—scared, bribed, both.

Inside the blackened tower, near the entry, was a ground-floor apartment. Here a short swart man strutted in, followed by a mouse of a woman painted up like a billboard. The man was Big Baby—a quarter Puerto Rican, a quarter Turk, two-fifths Negro, the rest miscellaneous. For a look he kept a pacifier in his mouth and curlers in his hair. He set his takeout chicken and jelly donuts beside a bare mattress. He lit a Sterno can for ambiance. A puddle of light spread from the wick.

“Please, Baby,” said the harlot. She ran her shaky press-on nails over her arms. “I’m hurting real bad.”

Wet gold flashed as Big Baby smiled. He drew a fat knife and stabbed a wall. The handle took his cheetah coat. At the window he parted the Hefty bag curtains and threw open the broken sash. In came a draft of filth. A garbage strike was on. To Big Baby it smelled like payday.

Big Baby turned back around, his gold teeth tight on the sucker. He reached down. A zipper spoke. The harlot’s eyes went wide.

“Feast those eyeses, child,” he said. He held his asset out to the Sterno light: a paper twisted at both ends, the load within no fatter than the snout of a rat. Also, he had taken out his dick. “The fo-real deal. Aca-ma-pulco Gold. Straight froms the Promised Land.” He meant Mexico. “Ninety-nine and foaty-fo one hunnerts percent pure, know what I’m saying?”

This was all a mumble through the sucker, and a speech impediment, but the whore was all eyes and few ears. And two knees, which she now went to. It showed initiative, Big Baby thought. “Oh yes, please, it’s just what I need,” she said.

In a fit of giggles, Big Baby missed the uproar right outside. Dopers and dope dealers breaking into a run, shouting, screaming. A honking horn, the swoop of a trash can in flight, a shatter of glass, a gush of malt liquor. It was the sound of a coming storm. A storm that walked on two feet like a man. A man with a right like a wrecking ball. A wrecking ball long overdue for the demolition.

Big Baby said, “Let’s us opens the flo to a bit of … negotiation.”

“So a blowjob?”

The window burst. Big Baby spun around and the whore fled, scuttling into the dark. What the dim light first made a wet sack of garbage was actually Sir Weasel in his bespoke velvets. A member of Big Baby’s own street gang, the Ladykillers. He had been left outside to keep watch while Big Baby got his checkup—him, Man Sam, and Poppin Snake. A shard had cut Sir Weasel’s throat. The lifeblood shot out onto the boards in farting pulses. Phbbt! Phbbt! Phbbt! His hand went limp. A .38 tumbled free.

Big Baby tucked himself away, but his sudden soft-on had done most of the work for him. He took up the gun and ran into the hall. He thought twice, came back in, threw on his furs, pulled the knife, primped his curlers, and ran out again.

Too late. There in the unlit and blackened entry stood a shape. A figure cast tall and broad by the flickering street lamp in the background.

Big Baby ignored the animal fear and brought up the weapons. He spoke through the pacifier. “Just got yoself a discount. Don’t you know where you at? This Pipe’s house. This where the Pipe play. And now you gonna pay too. Pay to play.”

Without a pause to ask for clarification but slow enough that Big Baby could finish his thought, the figure stepped in. A patch of light from a lamp in the stairwell crossed the beefy chest. The clothes were pitch black except at the very front of the collar. A single square of white. A white now flecked with red, a windowpane where the blood of atonement showed in the dark.

Big Baby thought, A priest? Couldn’t be—

But the man came on, the patch of light moved up past the collar, the iron jaw, the copper mustache. To the eyes, where it held.

Father Dukes!

The rubber nipple fell from Big Baby’s mouth. The .38 shook in one hand, and the knife in the other. His knees had turned to warm water. Actually he had pissed himself. His polyester socks squished as he took a step back. That fierce blue, that fire. This mother be crazy!

And that was Big Baby’s last thought before a fist knocked the curlers from his hair.

Atta boy, Mick! a raspy voice said. You showed dat schwartze what’s what!

Lefty Sofer had been his cutman back in the prizefighting days. The crusty yid had gone to glory not long after, or to a cozy nook of hell. But death hadn’t stopped old Lefty from chiming in.

And watch the footwoik!

The Reverend Michael Muldoon, better known as Father Dukes, stared down at his limp and bleeding handiwork. He plucked a tooth from the callus on a knuckle and threw it over a shoulder.

The priest was in a fury—a rage as red as the hair atop his head and fanned out upon his lip. He hadn’t felt an anger so deep since his final bout as “Dukes” Muldoon. His famed “sucker hook” had given the challenger brain damage. Wally “Twos” Phelan had been a gentle giant and a swell guy—not bad for Black Irish anyway. And though he had never been too sharp—he took “Twos” because he could count no higher— he hadn’t deserved a diaper and a padded ward.

The champ had thrown down his gloves in disgrace. He had sworn to his dying mother that he would enter the seminary to make amends. She hadn’t asked him to—had met the suggestion with a silent roll of her stroked-out eyes—but it had seemed the right thing to do. He couldn’t remember a seminary, but he was punchy himself and that was beside the point. He had the collar, the book, and a flock to tend, there in the seamy streets of Delaware City.

Father Dukes had served as an ambassador of sorts for the neighborhood families. The gang lords of the Killing Floor knew his name, his past, and better than to cross the paint at West 44th. And the priest had let himself feel content—to let the scum bubble as long as it kept to its toilet, a toilet being optimal placement for bubbling scum. But somehow Jenny Stupek, five years old, the cutest Polack you ever saw, had gotten her hands on the “product” and taken it for makowiec. Now she lay in a hospital bed, a tube up her nose, while bags dripped into her and a heart monitor peeped like a sickly bird.

Rage. Rage!

The priest reached down. With a single hand he hauled Big Baby upright and floppy, a leisure suit full of chewing gum. He held him against a charred wall and slapped him awake.

“Where is the Piper?” Father Dukes roared. The Piper, the mystery man, Delaware City’s “King of Boo.”

Big Baby had reached up to his hair. “My treatment!”

“The Piper! Where?”

“O.K., O.K., holy rolla. Pipe be upstairs, alls the way ups top. But you never make it.”

“And why not now?”

“The flos, they guarded. Each one mo thans the last. Mo guns, mo weapons.” Big Baby smiled short of teeth, working up the nerve. “Mo pain.”

A swoop to the chin put Big Baby through the cindered wall. His lifts dangled from the hole, shivered, went still in the sift of ashes.

You gotta step it up now, boychik! Lefty said from eternity. Timin’ is everything!

Twelve floors. Like the Stations of the Cross. And at the last came the nails, right? His mustache took a curl and his eyes a feral glow. He could hardly wait.

[On the next three floors, Father Dukes faces the last of Big Baby’s gang, a zombie-like horde of junkies, and an evil rock and roll band, in that order. —Ed.]

but the fire hose held. A last lunge got Father Dukes up and over. He crashed through the upper story window in a burst of glass, rolled, halted in a crouch.

As his head cleared he stood, coughing, patting out the flames on his clergy shirt. Absently he yanked the drumstick from the wound in his thigh. When the bloody shaft fell from his grip there was no clatter, no ring of wood on bare wood. It was then that he noted the carpet at his feet. Brand new. An undyed and slubby wool pile. Tasteful, some might say. That much was lost on the street-smart priest, who slept on under-washed rebar with a cinderblock for a pillow, but the pattern in the brocade was not: cocks and cherubs in a frolic. There seemed to be some kind of subtle message in it.

I gotta bad feeling about dis, said Lefty, and he wasn’t alone.

The priest took a jolt from his hip flask as he looked about. There was no sign of old smoke, no char, only fresh paint and a minimally furnished open floor plan. A sea of low shag, sprawling marble countertops at an island wet bar, recessed ceiling lights, a pit with a circular sofa. Conversation pieces, floral arrangements, very important works of art. Someone had not just rebuilt, but … redecorated. At the perimeters were window treatments—a lace of sorts—one of which he had knocked loose with his crashing entry. It lay on the carpet like a spurned bride.

Father Dukes thought it looked like an airport lounge, where fancy jets flew fancy people to parts unknown. So at first he took the three slinky figures lounging in the pit for stewardesses. They were sprawled about a glass table loaded with wine spritzers and plates of crab rémoulade with rocket and endive. Father Dukes saw only low tide on rabbit food with a side of sissy. But then the three stood, and even for all the vamping fuss of their movements, the priest saw that they were no ladies.

The three formed a delta, fists set high to hips, elbows out. The one in front wore a double-breasted silk frock and took pursing sips of smoke from a cigarette holder, theater-length. His glossy black hair bore a bolt of witchy white, curlicued at the end. The two behind him wore tight striped jersey shirts, capri pants, no socks, and side-gusseted dress loafers.

He in front took up a quizzing glass on the end of a waist chain and gave Father Dukes the once-over, pinkie akimbo. “Black, before Labor Day?”

Nancies! Lefty said.

One in back said, “He’s made a dickens of the drapes.”

“I’ll fetch the club soda,” said the other, looking at the carpet behind the priest.

“Hold off for now, Beauregard,” said the leader. “We’ll be needing more than just a spot treatment.” The three had fanned out.

“Mama told me not to pick on girls,” said the priest. “So why don’t you show me the stairs and swish yourselves on down to confession at St. Mary’s?”

“Where do you think we started?” said the leader.

“I’m here for the Piper,” Father Dukes said. “Stand clear.”

The priest made to walk between the leader and the man to his left. He found himself flat on his back, the print of a loafer in the side of his face. Father Dukes sat up, shaking light back into his head. The three tittered.

“You’re no garden-variety finook, are you?” the priest asked.

“I see what you did there,” said the leader. On the priest’s blank stare he sighed. “This is a dojo,” he said, rolling the j like a grape in his mouth. “I am Master Anton, and these are my disciples. Scott, Beauregard, bring me the mustache.”

“Yes, sensei,” the prettyboys said as one, and the sound was like a calliope leak.

“I’ve fought kickers before,” Father Dukes said, jumping upright.

“How about twirlers?”

As Master Anton said this, his disciples brought out weapons from behind their backs. Like the batons of majorettes but broken in half and rejoined with fine chain. And lacquered vivid pink. These they spun fast, changing hands, eyes and smirks locked on the priest through the flesh-toned blur.

Take care, pisher! Lefty said. Dese faygeles, dey got a talent!

Father Dukes could take a punch as well as he could dish one out. So he simply raised his forearms, covered up, and let the beating begin.

The queers swooped in, a wind ruffling the cuffs of their capris. The pink nunchucks caught the momentum and struck all the harder. The blows stung to the core. And again. And again. If the priest hadn’t kept so thick a brace of muscle through clean living and steak dinners, bones would have shattered, organs burst. But he tensed up and took it all, a human fist. And in his clench he let his uncanny pugilist’s sense study up as the assailants leapt and swung, yelping like minks in a pique. Each blow, each angle of attack went into the primal machine of the fighter’s mind. He listened through the drum of their weapons on his own body to where their feet landed, to the speed of their leaps and swings, the rhythm of it all.

Father Dukes stood up, straighter and straighter, dropping his guard, inviting the killing blow to his head, proud, red, and unprotected.

They took the chance both at once. At the height of their arcs his hands shot out. In an instant he had clamped the he-minxes by the throats.

Their bodies below the neck flailed like crash dummies, and the nunchucks shot from their grips. The table broke and drenched the carpet with rémoulade and spritzer. The fatales barely had time to choke on the crushed pulp of their voiceboxes before the priest clapped their heads together like strangely ripe bowling balls.

“Oh pickles,” said Master Anton. “And just when I’d got them both trained.”

“That chop-socky wasn’t so hot for the d.”

“I wasn’t referring to martial arts.” Master Anton threw aside his cigarette holder and brought up his hands. The fingernails were long and sharpened to points. “I’ll scratch your eyes out.”

And just like that Master Anton came on like a whirling dervish. Father Dukes barely brought up a forearm before a gash opened through the sleeve of his clergy shirt. The assailant leapt past in a garish grand jeté.

Father Dukes turned and hunched low, waiting for the cartwheel to double back. When it did in a blur he tried an uppercut. But the master flowed through the strike like a saucy eel, leapt, sashayed, and landed square on the priest’s shoulders.

The ankles were crossed at Father Dukes’s chest. Supple thighs clamped down on his airway. The thick muscles of his all-Irish-American neck fought back like tackles in a scrimmage. He clenched his eyes shut as he heard the nails swoop in. They raked against his lids. Even there the priest had steel, and the claws did little more than mark the map of his prizefighter’s scar tissue.

It was not fear of blindness that made the priest move but embarrassment: at his nape and through the silk pants he could feel the rage erection, probing, seeking a way.

“Gah!” Father Dukes threw Master Anton through an urn of daffodils. But the sleek homo landed in a handstand among the shards and petals, legs wide, pup tent pitched. Father Dukes rubbed the back of his neck, wishing for a grill brush and lye.

Nimble little shaygetz, ain’t he? Lefty said. You gotta use the overhand right!

“You told me never to do that,” Father Dukes said.

Master Anton came to a halt. “What’s that? I told you what?”

Don’t klatsch with the creep, just use the overhand right!

Getting no answer, Master Anton huffed and resumed his dance. And with a shriek like a banshee in a cathouse on dollar day he shot toward the padre.

Now!

Father Dukes felt the power flow into his shoulder and the opposite foot. Time slowed as the punch reeled out. Pie-eyes and man-talons filled his vision, an intersex harpy on the kill. And then he saw his fist connect in a flare of white adrenal light.

The priest came to from his pugilist’s trance, still standing, breathing deep. He looked down. The kung-fu master had fallen face up. The jaw had not only broken and dislocated but come half off in a ragged tear. The tongue lolled through the raw split aside the head. Master Anton sputtered, shook, went still in a mist of blood.

Father Dukes made the sign of the cross and went to find the stairs.

[Floors six through ten: starved rats, Senegalese mercenaries, “The Australian,” a brainwashed heiress with a machine gun, plus minions, and a Universal Life Church minister and his “love congregation.” On the eleventh floor, Father Dukes beats a knife-throwing witch doctor and comes up to a mysterious door. —Ed.]

bare steel in a steel frame, no handle, no rivet, no weld. Behind him Father Dukes heard the death rattle as Dr. Tsetse went limp upon the sewage pipe that had skewered him to the wall.

The priest was about to punch the door when he heard a metallic buzz and the pop of an automatic bolt.

The door stood ajar.

An invitation? No: a trap, an obvious trap. A wad of cheese on a wire that a rat would blush to sniff. But Father Dukes saw no other way. He was dog tired. His hip flask had been drained dry. Little of his clergy shirt remained except the scrap of black around the collar. And his bared and rippling torso told the story of battle. Cuts, burns, purpling bruises, bites (junkie and rat), boomerang welts, a cauterized bullet hole, a hickey. His suffering had a touch of Bartholomew and a bit of Matthew thrown in with a dash of Pete. All he had to do now to stand by his word—to get himself in good with the Almighty Referee and atone for his poor sportsmanship—was throw himself onto a crucifix and be a goddam man about it.

“Thy will and all that,” he croaked, and pushed though the doorway.

Nothing showed at first, the light too dim, but the musk in the air was dank and heady, jungle/vaginal. Some kind of herb or spice. Father Dukes didn’t know what sort—his “pantry” (the top of a stove) held salt, rock salt, and whiskey salt (a cooking experiment). Maybe it was sage. His mama had put sage in the corned beef one Thanksgiving, that and a Pall Mall butt. “Call it a toy surprise, you foakin’ gobshite,” she had said, falling boozily asleep at the table.

He had been shuffling forward one foot at a time to seek a path in the here and now, and flood lights switched on mid-step.

Once he blinked away the sear of white he saw where he was: a warehouse of sorts. A clear lane lay ahead. To either side of it the floorboards were heaped high with pure, drab “maree chhhuana” (as the Puerto Ricans said). Stacked the way the city priest imagined hay might be, and were it hay and this a farm, enough to feed every steak-beast for miles.

He walked down an aisle between the mounds, eyeing it all. So much! The source of the Killing Floor’s plague, this, the devil weed. A sweat came to the priest’s freckled brow. He stepped lightly.

A chuckle echoed through the grass. Father Dukes stopped and crouched, ready to punch the very air.

“Behold … my empire,” said a tinny voice. Father Dukes looked up and saw a P.A. speaker. And a video camera that turned to track his every move.

“Straight ahead, you’ll find a stair,” said the P.A., “and up the stair you’ll find me. I’ve been expecting you, Reverend Muldoon. It’s time we met. I made macaroons.”

The priest did not recognize the voice, but he knew whose it had to be. He felt a thrill. One way or another, soon the hunt would end. The Piper unmasked. And punched in the head.

The stair came up a trapdoor in the middle of the floor. The space above was a simple one. An expanse of floorboards; a spotlight in the middle; a desk in the light; a man at the desk. All else was darkness.

Father Dukes could scarcely make out a face behind the glare. And there were stacks atop the desk to block the view—stacks of bundled money, heaping, overflowing, piled like sandbags for a flood.

“Let me introduce you to the family,” said the voice, still amplified by a P.A. “Andrew, Ulysses, Benjamin. And Grover, sweet Grover. You can have the Abrahams.”

Father Dukes heard a click. Behind him the trapdoor sealed. Another click brought on the house lights. The priest looked about himself, puzzled. All around were ropes in four parallel rows, tied at four corners in turnbuckles. He turned back to the desk. “It ain’t regulation,” he said.

The figure stood from his switchboard and microphone. “Nor am I, Reverend.”

Father Dukes took a step back. “You!”

Him! Sheldy Pipowitz, Esquire. The shyster. The public defender who got the worst scum off on any technicality and sometimes (rumor had it) with a bribe. Delaware City’s “Voice of the People,” as his bus bench ads said. The oily, hook-nosed, thick-fingered—

What are you gettin’ at? Lefty asked.

“If I and my money might enjoy your … full attention, Reverend Muldoon,” Pipowitz said.

“What for? Pretty soon you won’t have a take to count. You’re gonna be counting to zero, like this: Zero. The end. Forever. And what you never counted on was me making it through your goons, one floor at a time.”

A grin, a chuckle. “It is precisely what I was counting. On.”

Father Dukes stared.

“You’ve been a thorn in my side for far too long, Reverend,” said the Piper. “And now the stages of battle have worn you out. With you gone—”

“So I should just, what, stand here while you wrap that up?” Father Dukes said. He cracked his knuckles and then his neck. He could go another round or ten.

“Oh.” The Piper pushed aside a stack of money. There on the desktop was a button and a bell—a ringside bell. The button he pushed straight away. Then he took up a carpenter’s hammer.

Somewhere past the ropes a panel opened up. Father Dukes heard a heavy trudge. Someone, or something, growing near.

“The short of it was, I gave the shiksa the dope, that made you mad, and your anger brought you here,” said the Piper. “All a part of my plan. All below, that was just an appetizer for—”

“There’s really no reason to yank on my rosary and let you talk,” said the priest, “when I can just ease on over and dot that ‘I.’”

“Well, I do have a gun.” He opened his wide-lapel coat. In a holster was a sizable revolver.

“And you didn’t just shoot me because why?”

“I don’t follow you.”

Gun, shmun, thought the priest. He had already taken a bullet that evening, and he had found it kind of fun. Of course that had been from the hot chamber of a busty heiress. He was curious, he had to admit. The clandestine dope overlord had gone to a lot of trouble. It seemed kind of rude not to wait it out. See what happened.

What happened was this: a shadow loomed on the other side of the ropes, at a corner. As it stooped and climbed through with a leaden energy, it came into the light and took a stool.

Father Dukes gasped. “Twos!”

Wally “Twos” Phelan. He had more than a foot on the priest and had lost none of his hulking power. His shoulders rippled with the ready force of a testy elephant. But he had no life in his eyes, his hair had fallen out, his skin had paled to ghostly white, and a scar stood out on his forehead and scalp where the doctors had worked to save the brain. Seated in his corner, he looked like a Frankenstein in a diaper.

“Say hello to my champion,” said the Piper. “I fetched him out of the V.A. a year ago and began his training. More like a circus bear than a ballerina. But memory did most of the work. Or what memory was left after you made applesauce.”

The Piper brought up the hammer and swung. The bell rung, and the old familiar peal went up Father Dukes’s backbone.

And not just his, it seemed. Twos came up from his corner, fists ready. Suddenly the brain-damaged heavyweight’s eyes had more light to them—almost a focus. And what they were looking at was Father Dukes.

“Wally,” said the priest, “listen up. It’s Mick. Mickey Muldoon. You don’t—”

On he came. A great arm swung. Father Dukes scarcely had time to feint and bob. The wind from the miss blew his hair back. It was as if a city bus had leapt past his head.

The Piper rang the bell again. Phelan went blank, turned around, and returned to his stool. Father Dukes stood his ground, catching his breath.

“Take a moment to reflect,” the Piper said, “on everything that led you here. On every gear and mainspring I had to put in place in order to make this timepiece run.”

Timepiece? That reminded the priest.

“Do you have the time, Mr. Pipowitz?”

The Piper sneered, rolled up a sleeve. “A grown man in need of a wristwatch. Look at this one, right here. Note the gleam—the refulgent splendor of precious gold. Twenty-four karat, encrusted with diamonds. A masterpiece of horology, it costs more than your entire parish—”

“But does it tell the time?”

The Piper was about to answer, or gloat some more, when the whole building shuddered. Stacks of money fell from the desk. The Piper grabbed the corner and looked around in bewilderment. Phelan yawned on his seat and let out a string of drool.

“Never mind,” said the priest. “It’s straight-up midnight.”

“What have you done?”

“I left my poor-man’s watch downstairs, you see, on the ground floor. To time a bomb—a firebomb. Jellied gasoline and white phosphorus. Got a little help from my republican uncle. Also I scraped off a lot of match heads. By now the flames are to the third floor. What the devil started here, God will finish.” The priest winked. “God or his palooka.”

The Piper reeled back in horror.

“But please, do tell me more about that fine gold watch.”

In a panic the Piper swung the hammer. The bell rang. The colossus rose.

Father Dukes’s attention went to his own defense. One well-landed blow from the retarded juggernaut would kill him outright.

The Piper had taken a walkie-talkie from the desk. He was screaming into it: “Send the helicopter! The chopper! Now!”

A ham fist shot for the priest’s head, then another. He weaved and ducked, stepping back.

He’s got a reach on him! Lefty said. You gotta swarm in and use it!

“Use what?” The priest pedaled back from an uppercut.

You knows what!

“No. No! Not that, Lefty! Never again!”

Dis time it’s different! It’s for the best, boychik! Look! The Piper, he’s gettin’ away to the rooftop!

The priest spared an eye. Pipowitz was nowhere to be seen.

The glance cost him. Phelan half-connected on a jab, and it sent Father Dukes hard into the ropes. They twanged like bowstrings and threw the priest back toward the shambling behemoth. One arm shot forward like a battering ram. A quick slip got Father Dukes under it but put him off-balance. He rolled on the floor and came upright. Smoke was already leaking up between the boards, he saw.

No time! said Lefty. Think of the goil. The goil!

The image came. Sweet Jenny Stupek. One time a lightbulb had burnt out in a lamp at the church. Without being asked, the little girl had dragged out a foot ladder and climbed it, trying to put in a new bulb for her manly priest. She had met her inevitable failure with a cute stamp of her foot and a squeaky humph! If only she’d brought two more little Polacks to turn the ladder for her and the bulb in her hand. Those golden ringlets, now spilled onto a hospital gown. A tube up her nose. The foam on her rosebud lips. The whites of her eyes shot with red. Her little body convulsing from the overdose. The reefer. The Piper’s venom.

Father Dukes screamed in fury. Phelan had come up close, a mighty fist cocked.

Time slowed as the maneuver began: the dreaded “sucker’s hook.” Father Dukes twirled his left fist to draw attention, and then sent it out at arm’s length to one side. The dopey giant’s eyes tracked it all the way out, and he turned his head, opening the sweet spot. Then came the right, a searing blur like a meteor strike, so hard that the fighting priest himself blacked out on impact.

He came out of the battle trance. The force of his own blow had knocked Father Dukes flat onto his back. The right arm lay useless, the wrist broken, the fingers curled up like the legs of a dying roach.

Above him the colossus towered. In the side of his head the fist print showed: the shape of knuckles in flesh and bone.

But the eyes were more lively now. Sleepy but there. Phelan glanced about. Something knocked loose had been jolted back into place.

Phelan glanced down, saw the priest. “Mickey?” he whispered.

But then the damage had its way, and Wally “Twos” Phelan fell once more, face forward. He struck the boards as hard as a timber. Blood trickled from both his ears.

Even in his grief the priest saw that the smoke was really spurting now. He felt the heat through the wood. The fire had reached the cache of devil weed just below him. The smoke changed color and density, pouring up through the floorboards a rich and milky white.

Before the priest could rise, block his nose and mouth, he had drawn a lungful. The toxin entered his bloodstream and flowed into his brain.

And … wait. What was he doing here, hurt like this, and hurting others? Hate and anger were only pain, after all. He looked around him at the wreckage, the smoke, the prone body. He frowned. What did he accomplish by inflicting more pain except bring it back on himself under another mask? He would have to rethink his life.

Easy, kid! Lefty said. That’s the boo talkin’!

And what was that voice? So much was just illusion, a phantom of his own device. He, the sovereign being presently known as Michael Muldoon, was the seat of his own torment. But he could become a lotus.

No, kid, noooo! the voice screamed. But it was already fading, already gone.

He wasn’t even sure what a lotus was, but he knew he could be one. A voice from a far minaret was telling him so. By forsaking desire he could reach wisdom. The inner light. Perhaps he’d open a wellness center—

A clout, square on his head.

“Ow!” He rubbed at the welt, a pain all too familiar but unfelt for many years. He looked up.

There stood a vision of his mother in her Irish tam and shabby housecoat. Her hair the same red as his own, her face pinched, a rigor mortis of disapproval she had worn all her life. The clothes were charred and stank of sulfur. She waved the rolling pin and spoke in a brogue as thick as champ despite five generations in the New World. “Look at you, pinin’ like a foakin’ Loyalist twat! Find the man in you and get on that Haybrew cuntiballs!”

“Mama! Did the angels send you from heaven?”

She brushed a giant maggot from her housecoat. “Er, they did! They did at that! Now let’s see us some wab, you chape lousy faggot! Up and after him, boy!”

She had already become a smoke—plenty of which had filled the room, he now saw, along with the orange firelight fanning up between the floorboards.

“Love you, Mama,” he shouted.

Sheldy Pipowitz, Esquire, alias The Piper, stood at the edge of the roof. Looking down he saw only flames, and out in the night below, crowds that had gathered to watch. The heat blew back his curls and the brightness lit up his beady eyes. He backed away.

He turned around, looked to the nighttime sky. He could hear but not see the helicopter. All around him the roof tar steamed. Soon it would bubble.

His shirt, checkered slacks, and game-show blazer were stuffed fat, as much of the gelt as he could save. The Grovers had gone in first, secured in the front elastic and Y-fly of his underpants. He imagined the tickle of the presidential whiskers. Sweet Grover, second only to gentle Ben, who was stuffed down the back and reaching for the front. “Not now, you tease, we’re making our getaway!” Ulysses shifted under his shirt, a bit of nipple play. Too bad about poor Andrew, left down below. But Old Hickory had been through worse.

Pipowitz checked his gold Rado. It could tell the time in Monte Carlo, Beverly Hills, London, Paris, Rome, and Gstaad, but now all he cared about was the tick of the second hand. The chopper would only be another minute or two. His mysterious superior had sworn a five-minute exit. And his mysterious superior was never wrong, never late.

The lawyer’s eyes shot to the roof access. The stairwell. Orange light flickered within and smoke billowed up. He smiled and wrung his hands together. The priest could never make it through that. Even if he survived the final bout.

And yet the Killing Floor mastermind had a moment of doubt. The priest had shown some mettle. A bullheaded tenacity. And yes, the luck of the Irish.

A noise came from the stairwell even as the chopper blades became a clear beat and underlying whoosh. Pipowitz took a step back. The roofing tar stretched between his sole and his footprint like a strand of taffy.

Oh, right: he had a firearm. Pipowitz drew it from the holster and kept a bead on the stairs. “So much for your sweet science, you shillelagh-humping paddy sheep rapist.”

Behind him the smoking rooftop burst. He spun in time to see his doom: Father Dukes, sooty black, grinning wide-eyed like a one-man minstrel show of death. [The similes of Milt Walsh do not necessarily reflect the views of Bart Lessard or the editor and publisher of Blood and Tacos. —Ed.] His red hair had been singed down to a stubble and roof debris stuck to his shoulders. Sparks shot up from the exit he had just made, then the very tongues of the flames.

“Never could find the goddam stairs,” said the smoldering priest.

The Piper’s hand shook. The revolver tumbled free.

“Have you ever once shot that thing?” Father Dukes asked. “Set up a line of cans, maybe?”

The shyster’s eyes went to the priest’s deadly right. He saw that the arm was broken, hanging useless. “You’re out of the match,” he said, getting back his nerve. “A technical knockout.”

But the left came up, and it wasn’t empty. Gripped firm was the hammer the Piper had left below, the hammer used to strike the ringside bell.

“Wrong,” said the priest. “Round three.” He swung.

The whole oily wig seemed to dent, tucked into the cranium. The eyes popped from their sockets, bloody and agog. At first the priest thought the lawyer had stuck out his tongue. But the pinkish-beige and squiggly surface protruding from that open mouth could only be human brain.

Dead on his feet, the shyster fell aside, the hammer lodged in place. Wads of money fell from his collar and waist, flitting away on the heat-gust of the inferno.

“Now how about those macaroons?” said the fighting priest.

Cookies or no cookies he smiled, contented, ready for his victory pyre and a little family reunion. He was reaching for his hip flask—there might be a happy dribble in it yet, just a taste to tide him over before the pearly gates—when he saw the helicopter.

It came through the thickening smoke, hovering only ten yards off. The rotor wash cleared the view. The machine was not what he expected. Sleek, sinister black, with blacked-out glass. Not the sort of thing a sinful sheeny tightwad like the dead Pipowitz would choose for a rental. Instead it looked … bank-y. And fine watch or none, the Piper couldn’t afford bank-y.

The priest watched the machine. He knew he was being watched in turn through that inscrutable glass—he and the cash-stuffed corpse at his feet.

And just like that, the black helicopter pitched and sped off. Father Dukes watched its flight. A corridor that led straight to the high-rises on the far side of Delaware City. Looming like hell’s own fortresses. Well-defended fortresses that had to be, what, sixty floors each?

So it went farther up. Lower down. Whatever. Goddam it, he would have to live.

Dat’s the spirit, pisher! Take it all the way!

“Lefty! I thought you were gone!”

A shudder interrupted the reunion. The whole building groaned and leaned. A fireball roared up the sides. The roofing tar went ablaze.

The tenement’s boined through, Mick! She’s comin’ down! You gotta jump to the next roof!

“That’s crazy!”

Just like you, boychik! It’s one story shorter. If you rolls, maybe you won’t break your neck!

Father Dukes made the sign of the cross. Then he crossed his fingers. With a furious sprint, he shot toward the curtain of flames at the edge

[He makes it. THE END. —Ed.]

Bart Lessard is the fake name of a cranky loner. Here he has adopted a cranky loner persona through the use of a fake name. He is the author of Rakehell and The Danse Joyeuse at Murderer’s Corner, both out on Kindle.